May is Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month. In his proclamation, President Obama cited the accomplishments of Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders and acknowledged the difficulties that members of this community have faced both historically and in the present.

Let’s take a short trip through our nation’s case law to look at some of these difficulties. Your lessons in school might not have given you a complete picture on American history.

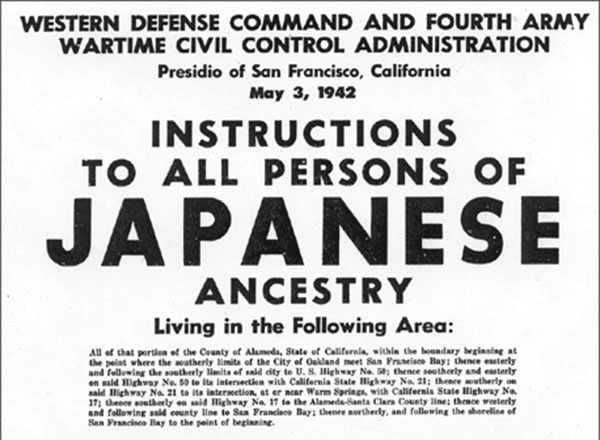

1. Korematsu v. United States

Photo Credit: National Park Service.

Fred Korematsu, an American citizen of Japanese descent, challenged his conviction for remaining in San Leandro, California, in violation of Exclusion Order No. 34, which required all persons of Japanese ancestry to evacuate from a designated geographical area. The Supreme Court stated that “legal restrictions which curtail the civil rights of a single racial group” must be subject to the most rigid scrutiny. “Pressing public necessity may sometimes justify the existence of such restrictions; racial antagonism never can.”

To justify the exclusion order, the Court cited the “definite and close relationship” between the exclusion order and “the prevention of espionage and sabotage.” The Court acknowledged the overinclusive nature of the exclusion order, noting that most of the people impacted by the exclusion order were “no doubt . . . loyal to this country.” However, the Court was not prepared to question the military’s judgment that “it was impossible to bring about an immediate segregation of the disloyal from the loyal” and upheld the exclusion order.

In dissent, Justice Frank Murphy acknowledged the deference that must be accorded to the military in its prosecution of the war. Nevertheless, the order by the military to remove all persons of Japanese ancestry from the Pacific Coast was not reasonably related to its claimed goal of preventing sabotage and espionage because the reasons offered in support of the exclusion order were based not on expert military judgment, but on “misinformation, half-truths and insinuations that for years have been directed against Japanese Americans by people with racial and economic prejudices.”

Even if “some disloyal persons of Japanese descent on the Pacific Coast [] did all in their power to aid their ancestral land,” “to infer that examples of individual disloyalty prove group disloyalty and justify discriminatory action against the entire group is to deny that, under our system of law, individual guilt is the sole basis for deprivation of rights.”

See Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944)

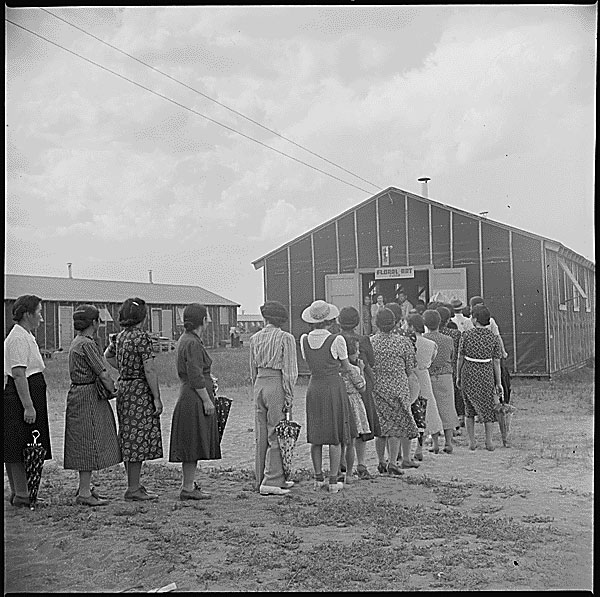

2. Ex Parte Endo

Photo Credit: Francis Stewart, War Relocation Authority, Department of the Interior / National Archives.

Ex parte Endo, 323 U.S. 283 (1944), is the companion case to Korematsu. Both cases were heard and decided at the same time. In Endo, the appellant filed a petition for writ of habeas corpus challenging her detention at the Tule Lake War Relocation Center. The Department of Justice and War Relocation Authority conceded that appellant was a loyal and law-abiding citizen, and did not contend that she may be detained any longer in the Relocation Center. While the Supreme Court stated that appellant Mitsuye Endo was entitled to an unconditional release, its reasoning was deeply unsatisfying. Instead of striking down the use of relocation centers on constitutional grounds, the Court instead held that the War Relocation Authority exceeded its authority under Executive Order No. 9066 by subjecting loyal and law-abiding citizens to its conditional release procedure.

Justice Murphy concurred with the decision, but again heavily criticized the majority.

I join in the opinion of the Court, but I am of the view that detention in Relocation Centers of persons of Japanese ancestry regardless of loyalty is not only unauthorized by Congress or the Executive, but is another example of the unconstitutional resort to racism inherent in the entire evacuation program. As stated more fully in my dissenting opinion in Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214, racial discrimination of this nature bears no reasonable relation to military necessity, and is utterly foreign to the ideals and traditions of the American people.

Justice Murphy further points out that even after the government provides Mitsuye Endo with her unconditional release, she will still be subject to the Civilian Exclusion Order that prevents her from returning to her home.

See Ex parte Endo, 323 U.S. 283 (1944). Also, view Precedent Decisions under the Japanese-American Evacuation Claims Act.

3. Oyama v. California

Photo Credit: Dorothea Lange, Department of the Interior, War Relocation Authority / National Archives

If Korematsu is viewed in isolation, the decision might be excused as an unfortunate product of war-time hysteria. In truth, the animosity toward the Japanese existed long before the date that will live in infamy. In 1913, California passed an Alien Land Law, which prohibited aliens ineligible for citizenship from acquiring, possessing, enjoying and transferring land.

At the time, only free white persons and aliens of African nativity and descent were eligible for citizenship. It wasn’t until the 1940s that naturalization was opened to “descendants of races indigenous to the Western Hemisphere,” “Chinese persons or persons of Chinese descent,” and Filipinos and “persons of races indigenous to India.” Takahashi v. Fish & Game Comm’n, 334 U.S. 410 (1948).

By 1952, an enlightened California Supreme Court recognized that “[b]y its terms the land law classifies persons on the basis of eligibility to citizenship, but in fact it classifies on the basis of race or nationality. This is a necessary consequence of the use of the express racial qualifications found in the federal code. Although Japanese are not singled out by name for discriminatory treatment in the land law, the reference therein to federal standards for naturalization which exclude Japanese operates automatically to bring about that result.” Fujii v. California, 38 Cal. 2d 718 (1952).

However, six years earlier, even the California Supreme Court was not as generous. In People v. Oyama, 29 Cal. 2d. 164 (1946), Kajiro Oyama, a Japanese citizen, had purchased land in the name of his son, Fred Oyama, a minor American citizen. The California Supreme Court affirmed a lower court decision that appellants’ purchase of the land in the name of his son was a fraud and a violation of the Alien Land law. Accordingly, the land escheated to the State of California.

The United States Supreme Court granted certiorari. In his petition, Oyama contended that the Alien Land Law deprived Fred Oyama of the equal protection of the law. The United States Supreme Court agreed, holding that the law treated minors whose parents are not eligible for citizenship differently from other minors. Its decision in Oyama represented a departure from earlier cases on Alien Land Laws.

See Oyama v. California, 332 U.S. 633 (1948).

4. United States v. Wong Kim Ark

Photo Credit: Immigration and Naturalization Service / National Archives.

Wong Kim Ark was born at 751 Sacramento Street in San Francisco, California, in 1873 to parents of Chinese descent, who were subjects of the Emperor of China. Both of his parents had permanent residence in the United States, and were carrying on a business here.

On a return trip from China, Wong Kim Ark was denied admission to the United States by the Collector of Customs on account that the Chinese Exclusion Acts prohibited Chinese laborers from entering the United States. Wong Kim Ark contended that since he was a citizen of the United states by virtue of his birth in San Francisco, the Chinese Exclusion Acts did not and could not apply to him.

The question presented by the record is whether a child born in the United States, of parents of Chinese descent, who, at the time of his birth, are subjects of the Emperor of China, but have a permanent domicil and residence in the United States, and are there carrying on business, and are not employed in any diplomatic or official capacity under the Emperor of China, becomes at the time of his birth a citizen of the United States by virtue of the first clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution, “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.”

The Court ruled that “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” excluded from citizenship only persons whose parents were diplomats of a foreign government or were members of an enemy in a hostile occupation. Otherwise, all persons born in the United States, including those whose parents were not citizens, still acquired citizenship in the United States upon birth.

See United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649 (1898).

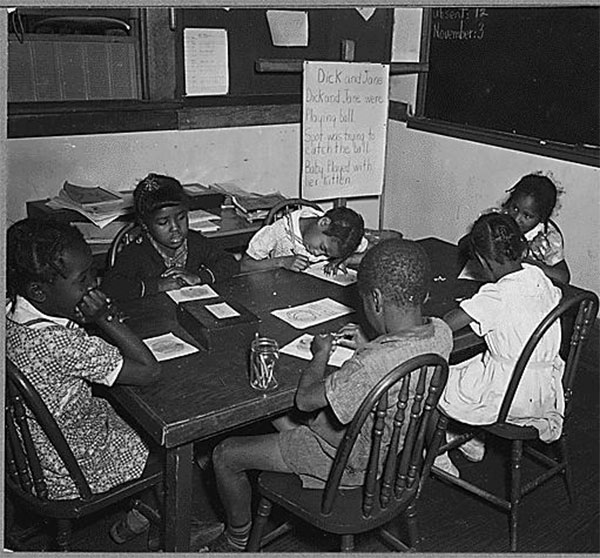

5. Gong Lum v. Rice

Photo credit: Irving Rusinow, Department of Agriculture / National Archives.

When we study the history of racial segregation in America, the landmark cases are Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896), which sanctioned “separate, but equal” accommodations and Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), which rejected Plessy v. Ferguson and found that “the doctorine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place” in the field of public education. So, what happens when a person falls outside of the traditional white/black dichotomy?

Martha Lum, a child of Chinese descent, was born in the United States and a U.S. citizen. Her father, Gong Lum, sought to enroll her in Rosedale Consolidated High School. In Mississippi, the state constitution provided that “Separate schools shall be maintained for children of the white and colored race.” Lum argued that his daughter was not a member of the colored race and since the school district did not provide separate public schools for members of the yellow race, she was entitled to enroll in the white public school.

The Supreme Court of Mississippi denied Martha Lum entrance into the white high school.

The legislature is not compelled to provide separate schools for each of the colored races, and unless and until it does provide such schools, and provide for segregation of the other races, such races are entitled to have the benefit of the colored public schools.

Citing Plessy, the United States Supreme Court affirmed the judgment of the Supreme Court of Mississippi.

In Justice Harlan’s famous Plessy dissent, he compared the court’s decision to the one rendered in the Dred Scott Case. He also cautioned that permitting such discriminatory laws would engender racial conflict in the future.

The sure guarantee of the peace and security of each race is the clear, distinct, unconditional recognition by our governments, National and State, of every right that inheres in civil freedom, and of the equality before the law of all citizens of the United States, without regard to race. State enactments regulating the enjoyment of civil rights upon the basis of race, and cunningly devised to defeat legitimate results of the war under the pretence of recognizing equality of rights, can have no other result than to render permanent peace impossible and to keep alive a conflict of races the continuance of which must do harm to all concerned.

However, Justice Harlan also had this comment, which suggests that the Louisiana statute governing the colored races did not apply to the Chinese.

There is a race so different from our own that we do not permit those belonging to it to become citizens of the United States. Persons belonging to it are, with few exceptions, absolutely excluded from our country. I allude to the Chinese race. But, by the statute in question, a Chinaman can ride in the same passenger coach with white citizens of the United States, while citizens of the black race in Louisiana, many of whom, perhaps, risked their lives for the preservation of the Union, who are entitled, by law, to participate in the political control of the State and nation, who are not excluded, by law or by reason of their race, from public stations of any kind, and who have all the legal rights that belong to white citizens, are yet declared to be criminals, liable to imprisonment, if they ride in a public coach occupied by citizens of the white race.

See Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U.S. 78 (1927).

6. Roldan v. Los Angeles County

In Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967), the United State Supreme Court reversed the convictions of Mildred Jeter, a black woman, and Richard Loving, a white man, for violating Virginia’s anti-miscegenation laws. Roldan, 129 Cal. App. 267 (1933), is the Asian American analogue of Loving, and highlights the ridiculousness of racial classifications.

Solvador Roldan was a Filipino man who had applied to the Los Angeles County clerk for a license to wed a Caucasian woman. The county clerk refused to provide a marriage license because California Civil Code § 60 provided that “All marriages of white persons with negroes, Mongolians, or mulattoes are illegal and void.” The question presented before the court was whether Filipinos were Mongolians for purposes of California anti-miscegenation laws. Instead of ruling on constitutional law grounds, the court proceeded on an adventure in statutory construction as it explored how the races were categorized. At the time, ethnologists divided mankind into five races: (1) white or Caucasian, (2) yellow or Mongolian, (3) black or Ethiopian, (4) red or American, and (5) brown or Malay. Finding that Filipinos were Malays and not Mongolians, the Court of Appeal affirmed the superior court order compelling the county clerk to issue a marriage license. In response, the legislature added Malays to California Civil Code § 60.

7. People v. George W. Hall

In People v. Hall, 4 Cal. 399 (1854), the appellant George W. Hall was convicted of murder based upon the testimony of Chinese witnesses. The question before the Supreme Court of California was whether such testimony was admissible. Where Roldan was an exercise in strict construction, Hall showcased unfettered judicial activism.

The statute at issue stated that “No Black or Mulatto person, or Indian, shall be allowed to give evidence in favor of, or against a white man.” Act of April 16th, 1850, § 14. Since the statute does not specifically bar Chinese, Mongolian or colored people from testifying against white people, the criminal verdict would appear to be safe. But, the court then proceeds on a curious interpretation of American history.

When Columbus first landed upon the shores of this continent, in his attempt to discover a western passage to the Indies, he imagined that he had accomplished the object of his expedition, and that the Island of San Salvador was one of those Islands of the Chinese Sea, lying near the extremity of India, which had been described by navigators.

Acting upon this hypothesis, and also perhaps from the similarity of features and physical conformation, he gave to the Islanders the name of Indians, which appellation was universally adopted, and extended to the aboriginals of the New World, as well as of Asia.

From that time, down to a very recent period, the American Indians and the Mongolian, or Asiatic, were regarded as the same type of the human species.

Did the court really have to go through this contorted reasoning? Couldn’t it just have said what it really felt?

The evident intention of the Act was to throw around the citizen a protection for life and property, which could only be secured by removing him above the corrupting influences of degraded castes.

It can hardly be supposed that any Legislature would attempt this by excluding domestic negroes and Indians, who not unfrequently have correct notions of their obligations to society, and turning loose upon the community the more degraded tribes of the same species, who have nothing in common with us, in language, country or laws.

…

We are of the opinion that the words “white,” “negro,” “mulatto,” “Indian,” and “black person,” wherever they occur in our Constitution and laws, must be taken in their generic sense, and that, even admitting the Indian of this continent is not of the Mongolian type, that the words “black person,” in the 14th section, must be taken as contradistinguished from white, and necessarily excludes all races other than the Caucasian.

Under this line of reasoning, I’m not sure why the court bothered with the Columbus tangent. They could have just interpreted “black” to mean “not white” and included Chinese people in their expansive interpretation. So much for Expressio unius est exclusio alterius.

8. Shelley v. Kraemer

In Shelley v. Kraemer, the United States Supreme Court ruled that racially restrictive covenants (i.e., private agreements that prohibit persons of certain races from using or occupying land) violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment.

One of the deeds in question contained this provision:

no part of said property or any portion thereof shall be, for said term of Fifty-years, occupied by any person not of the Caucasian race, it being intended hereby to restrict the use of said property for said period of time against the occupancy as owners or tenants of any portion of said property for resident or other purpose by people of the Negro or Mongolian Race.

I didn’t learn about racially restrictive covenants until law school. I am quite surprised that Missouri would even target “people of the Mongolian Race” since the 1940 Census found only 761 Asian and Pacific Islanders in Missouri. This total included only 74 Japanese, 334 Chinese and 16 Koreans. The rest were Filipinos, Hindus and others, which some courts do not consider Mongolian.

See Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948).

9. Mendez v. Westminster School District

Mendez is a California case that challenged the policy of several school districts to segregate students based on their Mexican or Latin descent. The court noted that “[w]e perceive in the laws relating to the public educational system in the State of California a clear purpose to avoid and forbid distinctions among pupils based upon race or ancestry except in specific situations not pertinent to this action.” Those situations referred to schools for children of Chinese, Japanese and Mongolian parentage.

Sec. 8003. “Schools for Indian children, and children of Chinese, Japanese, or Mongolian parentage: Establishment. The governing board of any school district may establish separate schools for Indian children, excepting children of Indians who are wards of the United States Government and children of all other Indians who are descendants of the original American Indians of the United States, and for children of Chinese, Japanese, or Mongolian parentage.”

Sec. 8004. “Same: Admission of children into other schools. When separate schools are established for Indian children or children of Chinese, Japanese, or Mongolian parentage, the Indian children or children of Chinese, Japanese, or Mongolian parentage shall not be admitted into any other school.”

The traditional narrative divided America between the free states and the slave states. After the Civil War ended slavery in America, we were taught that Jim Crow laws continued to segregate African Americans in the South with no mention that some of these same policies also existed in California.

See Mendez v. Westminster School Dist. of Orange County, 64 F. Supp. 544 (S.D. Cal. 1946)

10. United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind

In Thind, the United States Supreme Court had to decide whether Bhagat Singh Thind, “a high-caste Hindu, of full Indian blood, born at Amritsar, Punjab, India” was eligible for naturalization. At the time, only free white persons, “aliens of African nativity” and “persons of African descent” were eligible for naturalization.

As to what constituted a “white person,” the Court stated that white persons “imported a racial and not individual, test, and were meant to indicate only persons of what is popularly known as the Caucasian race.” However, the “[m]ere ability on the part of an applicant for naturalization to establish a line of descent from a Caucasian ancestor will not ipso facto and necessarily conclude the inquiry.” After all, we are all descendants of Adam, right?

In 1790, the Adamite theory of creation — which gave a common ancestor to all mankind — was generally accepted, and it is not at all probable that it was intended by the legislators of that day to submit the question of the application of the words “white persons” to the mere test of an indefinitely remote common ancestry, without regard to the extent of the subsequent divergence of the various branches from such common ancestry or from one another.

If having a Caucasian ancestor is not enough, what about someone actually being Caucasian? “The eligibility of this applicant for citizenship is based on the sole fact that he is of high caste Hindu stock, born in Punjab, one of the extreme northwestern districts of India, and classified by certain scientific authorities as of the Caucasian or Aryan race.” To get around that issue, the court states that “we must not fail to keep in mind that [the statute] does not employ the word ‘Caucasian,’ but the words ‘white persons,’ and these are words of common speech, and not of scientific origin.”

What we now hold is that the words “free white persons” are words of common speech, to be interpreted in accordance with the understanding of the common man, synonymous with the word “Caucasian” only as that word is popularly understood. As so understood and used, whatever may be the speculations of the ethnologist, it does not include the body of people to whom the appellee belongs. It is a matter of familiar observation and knowledge that the physical group characteristics of the Hindus render them readily distinguishable from the various groups of persons in this country commonly recognized as white.

See United States v. Thind, 261 U.S. 204 (1923).