We can’t send you updates from Justia Onward without your email.

Unsubscribe at any time.

From the New Deal of the 1930s sprang the administrative state. It was controversial then and remains controversial at times, but it’s here to stay. Justia provides a range of free resources to help Americans understand this complex area of law.

Nearly 40 summers ago, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its most famous decision involving the powers of government agencies. Issued on June 25, 1984, the ruling in Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. NRDC remains a cornerstone of administrative law. Justice John Paul Stevens wrote for the Court in devising a doctrine that has become known as Chevron deference. This two-step analysis applies to situations in which courts review an agency interpretation of a law administered by the agency. First, the court must decide whether the law clearly answers the question at issue. If it does not, the court must decide whether the agency interpretation “is based on a permissible construction of the statute.” This is not a difficult standard for an agency to meet, so Chevron marked a major victory for the administrative state.

However, the 2001 decision of U.S. v. Mead Corp. imposed a threshold requirement for Chevron deference. As Justice David Souter explained, the Chevron doctrine applies if the agency interpretation at issue “was promulgated in the exercise of…authority” that Congress granted to the agency to make rules carrying the force of law. Some legal scholars have referred to the Mead requirement as “Chevron step zero.” Further nuances have developed in the doctrine over time, making it more complex than it might sound from reading the original Chevron opinion.

Someone interested in the history of the Chevron doctrine can visit the Justia U.S. Supreme Court Center to explore the archive of landmark government agencies cases there. We also provide an Administrative Law Cases Outline in our U.S. law schools center to assist law students. In addition, the Justia Legal Guides include an Administrative Law Center that discusses how government agencies function more generally. This resource covers topics such as the various types of agencies, the steps for making regulations, and the administrative hearing process.

Types of Agencies

Agencies come in two main forms: executive agencies and independent agencies. Executive agencies include such powerful entities as the Department of State, the Department of Defense, the Department of Justice, and the Department of Labor. The leader of each agency is typically called a “Secretary,” and collectively they form the “Cabinet” of the President. Executive agencies and their Secretaries advise the President on important issues in both domestic and international spheres.

Meanwhile, some notable independent agencies include the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Whereas executive agencies usually have a single leader, independent agencies tend to be headed by a commission or board that consists of several people. As the name suggests, these agencies have more freedom from presidential control. For example, the President usually does not have absolute discretion to fire a head of an independent agency but can remove them only for good cause.

A handful of other agencies operate in the legislative and judicial branches. One legislative agency is the Library of Congress, which provides a research and information hub for Congress. The Federal Judicial Center serves a similar function for federal courts.

The Agency Rulemaking Process

Despite their differences, executive and independent agencies are similar in one important way. Both types of agencies must follow the rules provided in the Administrative Procedure Act (APA), which is found in Title 5 of the U.S. Code. Many of these provisions cover the process of agency rulemaking, which may unfold in formal or informal ways.

Formal rulemaking generally involves a hearing on the record, including the presentation of evidence. Fortunately for agencies, this relatively onerous process is not often required. Interpreting the APA, the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that an agency must conduct formal rulemaking only when the agency statute provides a hearing and states that it must be on the record. An agency must publish a notice of an upcoming hearing, and it may need to specifically notify people or businesses that will be directly affected by the potential rule.

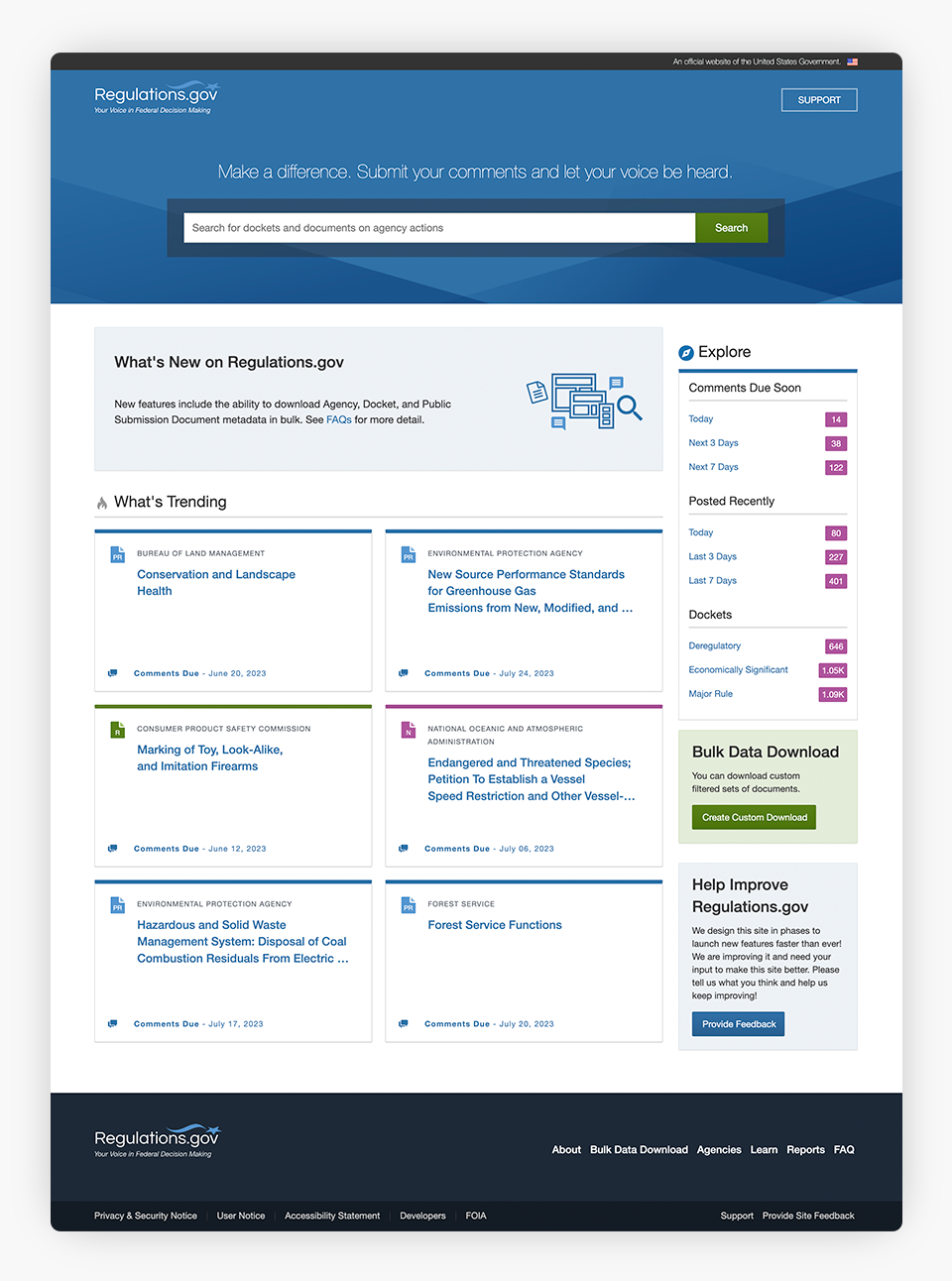

Informal rulemaking can proceed more efficiently because it does not involve a hearing. However, the APA imposes certain requirements for what is called the “notice and comment” process. The agency must publish notice of its proposed rule, after which the public can provide comments on the rule. The agency may revise the rule in response to the comments before codifying the final rule. In some cases, an agency may essentially rewrite the rule if it finds criticism of the rule persuasive. Then, it will restart the notice and comment process by publishing a new notice.

Administrative Hearings

Agencies may hold hearings not only during the formal rulemaking process but also when they adjudicate disputes. An administrative law judge usually presides over hearings. This is a federal official who is appointed based on merit and may be removed only for cause. Many agencies maintain permanent ALJs, while other agencies borrow an ALJ from another agency as needed.

An ALJ has substantial power because they decide both factual and legal issues in a dispute. In other words, there are no juries in administrative hearings. This might seem unfair because the ALJ is a government employee, but the APA preserves their impartiality by shielding them from agency pressure or influence.

If someone disagrees with an ALJ decision, they have a right to appeal. Generally, the appeal process begins within the agency. If appealing within the agency proves unsuccessful, a person or entity can pursue judicial review in a traditional court. However, courts generally show strong deference to agency decisions. The party challenging the decision may need to prove that it was arbitrary or capricious, for example, or they may need to meet one of the other grounds provided in Section 706 of the APA.

Final Thoughts

The field of administrative law may seem dry and esoteric to the average American. However, agency actions can shape the rights and duties of people and businesses. Someone who is facing an agency investigation, at risk of an enforcement action, or considering challenging an agency action should consult a lawyer for advice tailored to their situation. In the meantime, the Administrative Law Center provides a general overview of how agencies function. Like the other Justia Legal Guides, it aims to make the law transparent and accessible to all.

Related Posts